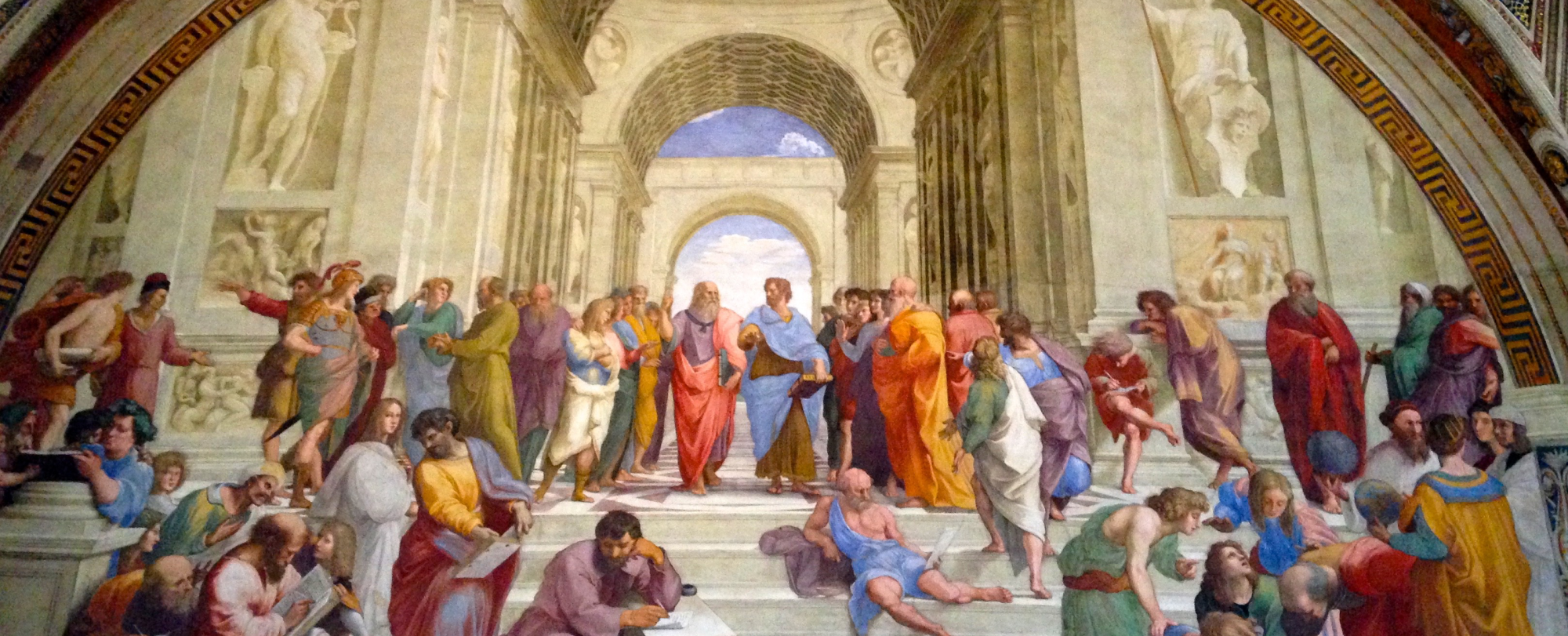

“Then this must be our notion of the just man, that even when he is in poverty or sickness, or any other seeming misfortune, all things will in the end work together for good to him in life and death . . . [to] any one whose desire is to become just and to be like God, as far as man can attain the divine likeness, by the pursuit of virtue?” 1

~Plato, Republic

Some may rival, but no thinker in history surpasses Plato’s influence on culture. A. N. Whitehead captured the essence of western philosophy stating, “the safest general characterization of European philosophical tradition is that it consists of a series of footnotes to Plato.” While Plato enjoys modest favor outside of Christian circles today, his worldview still exerts a gravitational force, but of a planet far away. His magnum opus, Republic, written about 400 years before Christ, presents a complete worldview in a provocative and enthralling dialogue about the just person and the just state.

Within these pages a stunning projection of reality beams forth in a world vision of all existence and knowledge, truth, beauty, wisdom, and justice. Plato envisions a spiritual supreme being as the Good and the Forms. The Good’s nature contains all these sublime and perfect concepts beyond, above, and outside the physical world. These good essences project into or participate in all physical things, but matter corrupts these pure essences. Matter degrades the essences of things. Essences consist of the pure ideas and concepts. These absolute and unchanging essences abide in the eternal mind of the Good.

Plato takes the gold medal for absolute truth and ideas because these have an absolute source in the Good. As humans, our flesh corrupts our pure spirit, leading us to do injustices. Salvation’s path follows the spirit and stifles the flesh and its base desires. The just person will control lusts, volatile emotions, passions, and base drives. This ascetic way will perennially resurface in cultural history. It profoundly influences Christian culture, doctrine, and practice through the centuries. You will hear professors say that you can’t be an educated person until you’ve read X. With Plato’s Republic this rings true. Yet, our age runs out of sync with Plato.

Today many scoff at Plato as a traditionalist or as a stubborn absolutist who believed in a fictional world of pure ideas. We live in an age that rejects essences. About 700 years ago, a powerful movement rejuvenated an ancient idea that Plato had confronted. Nominalism rehabilitated the idea that no essences exist.

Essences or universals became mere names and social convention, not pure ideas that exist independently and eternally. Zoom ahead to Darwin, 1859. Living things possess no fixed essence or nature because all biology evolves from one creature to the next. Thus our materialist age sees all things as fluctuating in random configurations of matter devoid of essences. Nothing is what it is. Rather, things are what we collectively choose them to be what we choose to name them as.

Drifting further into the mid to late 20th century, existentialism engulfed our culture and its flood still crests. “Existence precedes essence” proclaimed Sarte, beckoning us to believe our essence emerges from our physical existence and our choices alone. “Be all you can be.” Be whatever you choose to be. The weighty implications here must not escape you. So here we rest as a culture on the rocks, somewhere far down the river from the dock of transcendent and timeless truth, justice, and beauty. As a Christian, whether you agree with Plato or not (and many Christians have from Augustine to Lew-is), it isn’t hard to recognize that our shipwrecked culture disavows truth from outside, above, and beyond it-self whether from God, or Plato’s Good. Read Plato’s Republic to enter and engage the greatest conversation in history. Maybe you’ll write the next footnote.

1-Plato, The Dialogues of Plato, trans. B. Jowett, Third Edition., vol. 3 (Oxford: The Clarendon Press, 1892), 329.