“And surely that than which a greater cannot be thought cannot exist in the mind alone. For if it exists solely in the mind, it can be thought to exist in reality also, which is greater” (Anselm, Proslogion, ch. 2).

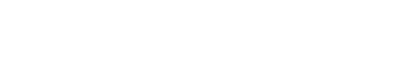

Anselm’s second chapter of the Proslogion is one of the most famous passages in the history of theology, philosophy, and Christian apologetics. Here he outlines one of the most intriguing and original arguments for God’s existence. First called “Anselm’s argument”, it was later renamed by Immanual Kant who coined the term “Ontological Argument”.

As Anselm makes clear in the preface to the Proslogion, he hoped to “find one single argument that for its proof required no other save itself, and that by itself would suffice to prove that God really exists.” The ontological argument is the result of this endeavor. Philosophers and theologians have been divided on this argument. Some think that he was successful. Others radically disagree. I’ll leave it to you to decide how you feel about it. For now, I’d simply like to highlight his argument and try to explain the key points along the way.

There are literally thousands of resources describing and commenting on his argument. In an effort to try to make his argument more clear, commentators often re-word or restructure his argument. I’ll try to avoid that. Here’s what he actually says.

- “We believe that You are something than which nothing greater can be thought.” In other words, when we think of God, we think of him as the greatest possible being that there could ever be. God is the kind of being that nothing could be greater than.

- “For it is one thing for an object to exist in the mind, and another thing to understand that an object actually exists.” This is actually rather simple. There is a difference between the idea of an object and the object itself in the real world. Anselm’s illustration for this is a painting that is imagined in advance by a painter, and the actual painting that eventually is created.

- “Even the fool…is forced to agree that something than which nothing greater can be thought exists in the mind, since he understands this when he hears it, and whatever is understood is in the mind.” Again, this is rather simple. Anselm is saying that everyone (even the fool who denies God’s existence) has the idea of God in the mind since we understand the idea of God when we speak about it. This understanding indicates that God at least exists in the mind.

- “And surely that than which a greater cannot be thought cannot exist in the mind alone. For if it exists solely in the mind, it can be thought to exist in reality also, which is greater.” This is where the argument gets interesting. Anselm notes that God (the greatest conceivable being) cannot just exist in our minds. He must also exist in reality. Imagine some being we call God that seems incredibly great, but note that this being only exists in our mind. Couldn’t we imagine a different being who is greater still because He actually exists outside the mind in the real world. Wouldn’t this be the actual God (the actual greatest conceivable being)?

- “If then that than which a greater cannot be thought exists in the mind alone, this same that than which a greater cannot be thought is that than which a greater can be thought. But this is impossible.” Here Anselm notes an absurdity. In short, it requires to say that we cannot conceive of a greater being then the God (who exists in the mind only) and that we can conceive of a greater being then God (who exists in the real world) at the same time. This is impossible, God cannot be both.

- “Therefore, there is absolutely no doubt that something than which a greater cannot be thought exists both in the mind and in reality.” By implication then, God has to exist in our minds and in this world.

This, in short, is how Anselm argues for God existence in chapter 2 of the Proslogion. Some people love it, some think it is a foolish game of smoke and mirrors. There have been later developments on this argument that we can explore later in different posts. But all versions harken back to Anselm’s original work and play on the idea of God as the greatest conceivable being. What you think of it is your call. But I, for one, remain fascinated by these kinds of arguments!